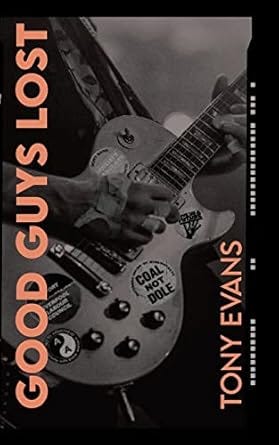

A Novel Idea: Assessing A Flop Two Years On From The Release Of Good Guys Lost

Would I have started the book if I'd have know how it would turn out? I'd like to say no but it's just another act of resistance to try and create left-wing literature in a right-wing world

“If you really like it you can have the rights

It could make a million for you overnight…

I wanna be a paperback writer”

Paperback Writer. The Beatles

TWO YEARS AGO yesterday, my first novel was published. A lot of people think they have a book in them. They may be right. This is what I learnt from my experience.

Good Guys Lost was a long time in writing. I had no real urge to start a novel until – bizarrely – I was watching I’m A Celebrity Get Me Out Of Here in 2004.

Two of the participants were John Lydon and Katie Price. Johnny Rotten and Jordan.

Lydon was talking to Price about the importance of cleaning the water container. Punk’s antichrist understood that there were certain activities that needed to be a communal enterprise.

Price couldn’t be arsed. Someone else would do it if she didn’t. So why the fuck should she?

A massive realisation struck me. Lydon was born in 1956. For all his anti-establishment image, he grew up in a Britain where people had a sense of responsibility to each other.

His campmate Price was born in 1978. By the time her opinions and personality were being formed, the political ethos in the UK was summed up by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher: “There is no society.”

These two people had a completely different philosophical approach to life. It struck me that before Price reached adulthood, a watershed in British life had occurred. Rotten believed in society. Jordan didn’t.

Lydon makes a short, pretty inconsequential cameo in Good Guys Lost. Price doesn’t. The book is about the forces that defined them – and many others.

The other main inspiration for the novel was Sir James Goldsmith. In a BBC series called The Mayfair Set – a three-parter that explains the genesis of Thatcherism – he says that some find the acquisition of money vulgar, but “vulgarity is sign of vigour.”

I realised that ‘Thatcherism’ is a misnomer. Her politics and policies are better described as Vulgarism.

So far, so boring, right? Well, the book might be about all this kind of stuff but the plot is a completely different thing. Music, gangsterism, a bit of football culture, phone hacking, reality shows and a portrait of Liverpool from the 1960s to about 2016 that, I hope, reflects the reality of working-class life. There’s even an album’s worth of songs that go with it.

I knew it was different. Publishing is a very middle-class business and most authors come from privileged backgrounds. So much of literature is complacent and smug.

By the time I finished the novel, it was the 2020s. In that period, I’d produced three non-fiction books. Well, I thought, being an ex-football editor of The Times, I had a fair set of credentials.

Yeah, right. From agents to publishers, the dismissive attitude and lack of professional respect stunned me. Not because I expected preferential treatment. I just didn’t expect to be treated like a prick. And the worst thing? If they were doing this to me, with a verifiable record of writing achievement, what the hell were they like with new, unknown writers?

In the end, I was offered a deal by a small, new publisher who wanted to specialise in northern writers. I’m not sure that some of the people involved ever understood what I was trying to do. They have got much better since those early days and I would advise everyone to check out Northodox books.

One story I will tell is about the editing process. I wrote two books for divisions of Penguin. For the first one, I Don’t Know What It Is But I Love It, the editor was superb. They emailed me to tell me how impressed they were with the standard of the copy, saying there were remarkably few mistakes. I was, after all, an editor myself. But, they mentioned, I’d used the word ‘brutal’ more than 80 times in 70,000 words. Splendid feedback.

I learnt from that. For Two Tribes, I had that in mind. A different editor told me it was the cleanest manuscript they’d worked on. I’d printed out, read and marked up errors in each book at least five times.

I did the same with Good Guys Lost. When the edited version came back, I was excited. Until I opened it. More than 1,200 changes.

The only thing to do was get two laptops and compare the manuscripts line by line. It turned out that 99 per cent of changes were adding the fucking Oxford comma.

Now, an important part of my fiction is the rhythm of the words. The editor did not understand it. In the entire work, there were two legitimate corrections. I’d transposed an L and I in Liverpudlian and not noticed an ‘on’ that should have been ‘in.’

Oh, and seven errors had been introduced in the first five pages because the individual concerned did not understand Scouse and a Merseyside upbringing.

I could go on. But the finished product was disappointing. So was its impact.

Now, I thought being in the media, there’d be some sort of ‘mates rates’ when it came to coverage. Nah. No one was interested. No reviews in the press. Nothing. If people thought it was crap, I’d be quite happy to accept the criticism. In fact, it would have been uplifting to know someone was at least engaged enough to care. But no. Nowt.

Except for Everton fans on Amazon reviews the day it came out. They slaughtered it. Not that any of them could have read it. Imagine being such a prick you’d try to destroy a working-class man’s career on the basis of your perception of his support. The main character in the book is blue, too.

But I don’t mean to come across as whingy. I’m not a person who feels proud about anything I’ve done. Life has taught me many lessons which were summed up, probably, in a line from the novel: ‘Defeat was our destiny but resistance defined us.’ That applies to everything from Hillsborough to my career. And screw everyone, the battle is still on.

Writing is the easy part. Any fool can do that. It takes time, concentration and having something to say.

Those who’ve read Good Guys Lost have loved it – or at least that’s what they say. It’s a rattlingly quick, pacy yarn, with two murders, a jawdropping female villain and international action – all underpinned by left-wing politics. The protagonist is a singer-songwriter who screws up his life. Would he have been a star if not for his violent actions? You can decide by listening to the music.

Would I have started it if I’d have known how it would turn out? Probably not. From my point of view, it highlights the worst aspects of my culture and background. I should have switched channels from Lydon and Jordan. Or pretended it was only a TV show.

Yet I wanted to write a book that challenged the reader. I just didn’t expect it to be so challenging for me. Anyway, here’s an extract from it and a teaser video.

Good Guys Lost: ‘A time when gangsters and footballers lived among the communities that bred and revered them’

‘Why shouldn’t working-class men dress well? Why shouldn’t working-class men wear nice suits?’

The boy would hear the phrase again almost two decades later, as a declaration of class war. But this was the first time it reached his ears. The speaker was his uncle, Bobby Moran, responding to a barmaid’s flirtatious suggestion that he was a bit ‘flash.’

Uncle and nephew had been to Anfield together for the match and had stopped at the Honky Tonk on Scotland Road because Bobby wanted to see someone. Nobody called him by his real name, though. He had long been known as ‘Duke’ because of a childhood obsession with John Wayne.

The nickname suited him. He had something special about him.

Perhaps it was the smell. Duke smelled of the gym, sweat, and power. Yet, all the pungency that drove people away was absent. It was an odour of distilled masculinity, a heady, magnetic scent with the merest undercurrent of threat that needed no cosmetic overlay.

Duke wore midnight blue kid mohair suits and had an aura of confidence that seemed borrowed from a different social class. Stolen would be a more accurate word, for he was a thief.

‘My name’s crime,’ he would say, while selecting whatever he wanted in a shop. ‘And crime doesn’t pay.’ Shoplifting was just the beginning.

The age of the Cunard Yank had passed, and the likes of Duke assumed the succession and the glamour, although their only voyaging came on the Seacombe ferry. Yet these were men who were also travelling beyond the limit of their horizons.

This was a time when gangsters and footballers lived among the communities that bred and revered them. Their income was maybe three times that of the average wage, and they lived in tenements, terraces, and semis in the suburbs. Some even felt responsibilities to those around them.

Most people thought Duke could’ve been either. Both of the city’s football clubs had given him trials, but the distinct and discrete mindsets of the gangster and sportsman were mutually exclusive, and Duke’s talents pushed him towards darker games than passing and shooting.

He was a natural athlete and boxed almost as well as he headed the ball. Early on, though, he knew he was not belt-winning quality. In the ring at Lee Jones, better boxers were scared of him. They knew that in the less subtle arts of street fighting, Duke was championship material. The head that drove caseballs towards the net crushed noses and shut down senses quicker than his punches.

By night, he donned the tuxedo of a doorman. By day he stole, progressing from the shoplifting of his youth to breaking into bonded warehouses. By the mid-1960s, he was branching out to sub-post offices and dreaming of a lucrative bank job.

His friends and accomplices had dangerous nicknames: The Gasman, the Panther, the Dog. They were feared figures.

Duke was born on December 21st, 1940, as German bombs rained down on the city. Just before the raid started, his mother went into labour with her fourth child, sirens howling their warning. The pregnant woman was rushed to Mill Road Hospital from the family flat in Blackstock Gardens. Neighbours ushered the other three kids down to the air-raid shelter in the block.

While Mrs Moran screamed in agony at Duke’s prolonged entry, a German bomb scored a direct hit on the flimsy shelter back home. There were hundreds of people inside: not only had locals flooded down the tenement staircases to find protection, two trains on the nearby line had been stopped and their passengers directed to apparent safety.

They lost count of the bodies after the two hundred mark because rescuers could not jigsaw the mass of limbs and trunks together in a verifiable manner. Two of the Moran children were never identified nor found. The eldest, Joey, was at the top end of the shelter, playing with a mate. When he recovered consciousness, ten-year-old Joey was trapped between his dead friend and an avalanche of rubble.

It was not the end of the family’s anguish over that grim holiday season.

Their father, in the Merchant Navy, would never hear about his children’s deaths or the birth of his son. He was in the engine room of the SS British Premier off the coast of Africa on Christmas Day when U-65’s torpedoes sunk the tanker.

His body was never found. The Morans were one of the many families in the area whose lives were destroyed during that dreadful December.

The sense of drama and tragedy which greeted Duke’s arrival into the world never left him. He followed in his big brother’s footsteps, working as a bouncer. Men feared Joey Moran.

During his adolescence, he became an expert fist fighter, honing his violent skills while on National Service; and after his discharge, Joey was recruited to man the doors of the more upmarket clubs in town.

Duke was different, even though he was almost as dangerous. He had a swagger his brother would never carry off. At twenty-six the younger Moran was widely admired and the Tate and Lyle’s girls swooned when he walked along Vauxhall Road dressed, with no exaggeration, to kill.

Wiser women, like his mother, despaired. Any wife he took would have to live dangerously. In love, like everything else, Duke did his finest work outside the rules, beyond the law.

Duke had an eye for trouble. He sensed it first and dealt with it; some said prematurely. Initially he avoided becoming a doorman, working in St John’s market, humping crates of produce on and off trucks before dawn for paltry wages and the odd box of unsold fruit. It didn’t take long for him to recognise his more unsavoury skills were worth being paid for.