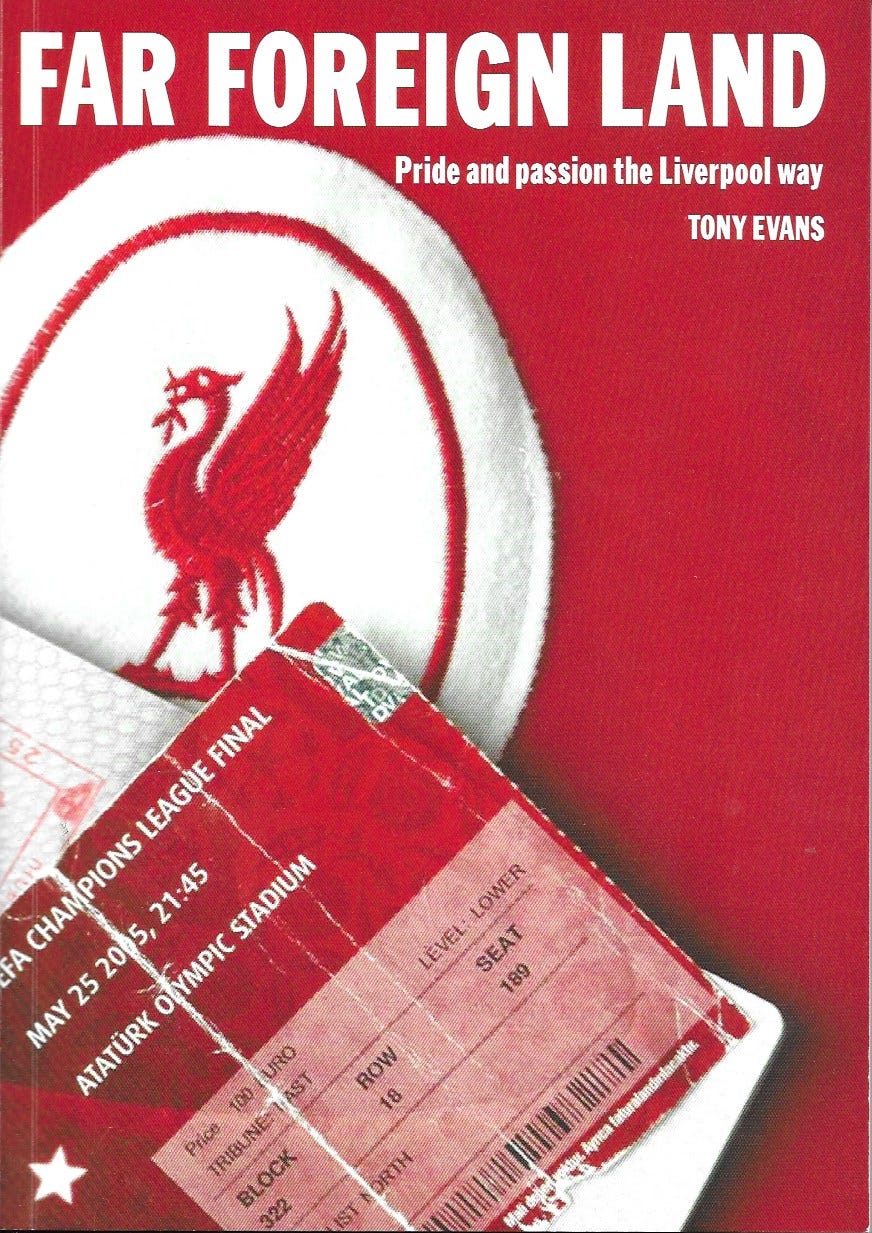

Book serialisation: Far Foreign Land, Chapter 17

The aftermath of the game. The blaring music, We Are The Champions blasting out when we should have been singing OUR songs. Uefa try to spoil everything

KAKA MAKES IT 2-2. Next it’s Smicer. This will be the final time he kicks a ball competitively in a Liverpool shirt.

He’s been abused, castigated, laughed at and despaired over for his entire career at Anfield. Heart rates are soaring around the stadium. Except for Smicer, who calmly slots the ball home. Now it’s Shevchenko. The best striker in Europe. If he scores, the pressure will be on the final Liverpool penaltytaker.

It’s a poor penalty and Dudek saves. The ball rebounds to Shevchenko.

Most people around me stand stock still, dreading that the striker will ram the ball into the net at the second attempt. In their nervousness, they’ve forgotten the rules. I haven’t. I’m standing on the seat letting one gigantic, cathartic howl of victory loose into the night air.

In the split-second before realisation dawns, a man in front of me, perhaps the only one in the stadium to hear my scream, turns and hugs me, hooking his arms around my thighs. He’s around my age, maybe older. This stranger holds me and, while everyone else suddenly goes crazy, we do not move.

After a few seconds he looks up, tears running down his face. ‘Twenty years,’ he sobs. A tear drops softly down on to his head. It’s a tender moment. Then he lets go, punches the air and runs across the seats to the front where the players are celebrating. I never see him again.

* * *

Four hours after the match, we were in an Irish bar. From Mersey to minarets in less than a week and we celebrate success against a backdrop of shamrocks and leprechauns.

This is normally the last place in Istanbul that we’d choose to visit but there is a method at work here.

After three hours standing on a cramped bus trying to get back into the city centre, we needed a drink. We were tired, emotionally drained and unable to comprehend the events of the previous night. Then Al piped up as the search for an open bar began.

‘I know an Irish place.’ Even before the sneers had stopped, he silenced them. ‘It has Sky Sports News.’

The one thing we needed even more than a drink was to see what happened. How it happened. We were still not really sure we believed it.

There were six of us now. Ian and Stephen went straight to the airport. We sat in silence, mainly. That’s about as rare as winning the European Cup.

Shock brought incoherence. Tony attempted to quantify the magnitude of what we had just seen. ‘It is like the best day of your life, only better,’ he said.

‘The way your wedding day is supposed to be, but isn’t.’

‘Well your wedding didn’t cause mass pain to thousands of Evertonians and Mancs,’ Dave said. This was an ingredient to be relished, the sweet dusting on the Turkish delight.

Rivalry brings such pleasure - and pain.

Dave had hit the jackpot. After all those years being the butt of jokes, he had seen a game, a victory, that will rank even higher than 1977, when the European Cup was won for the first time in Rome. It is the greatest night of all and he was there. Already, he was compiling lists of those who had mocked him in the past but not made the journey to Istanbul. Payback would soon follow.

Then the goals came on a big screen. As Crespo scored Milan’s third, Andy Gray, the Sky commentator, said: ‘That’s it. Game over.’

The bar erupted with a hail of invective. Gray played for Everton and is still regarded, two decades on, as the enemy.

For all the joy, there was discontent. Uefa did its best to spoil the trophy presentation and lap of honour. At a time when we should have been singing our songs, the public address system pumped out a deafening cacophony of pseudo-classical music, repeated versions of You’ll Never Walk Alone so that even we had too much of it and the appalling We Are The Champions by Queen. All at decibel levels that would leave Ozzy Osborne pleading for earplugs.

I mentioned that I did not hear I Am A Liverpudlian sung throughout the entire game. ‘Most of them wouldn’t know it.’ Stevie said.

This is a song some of us consider more pivotal than You’ll Never Walk Alone – after all, no one else sings it. It’s ours and it’s exclusive. But it came about through something other than marketing, from something outside the control of the people who run the game. They feel safer with Queen than the authentic voice of the fans.

When Steven Gerrard hoisted the Cup in front of us, this was what we should have been singing. Instead, it was: ‘No time for losers.’

Some of us remained bitterly silent but most joined in with the song. The irony is that the line could be the motto of the game’s authorities, who see fans like us in those terms.

At the other side of the bar, another loser seemed to have read our thoughts.

‘I will tell you the story of a poor boy,

Who was sent far away from his home,’ a voice began, slowly, unaccompanied, husky from overuse.

‘To fight for his king and his country,

And also the old folks back home.’

One by one, men around the bar joined in, each new vocal adding urgency as the pace quickened to the beat of stamped feet.

‘So they put him in a Highland Division,

Sent him off to a far foreign land,

Where the flies swarm around in their thousands,

And there’s nothing to see but the sand.

Now the battle it started next morning,

Under the Arabian Sun,

I remember that poor Scouser Tommy,

Was shot by an old Nazi gun.

As he lay on the battlefield dyin’,

With the blood gushing out of his head,

As he lay on the battlefield dyin’, dyin’, dyin’,

These were the last words he said:

Oh, I am a Liverpudlian,

And I come from the Spion Kop,

I like to sing,

I like to shout,

I get thrown out quite a lot

(Every week).

I support the team that’s dressed in red,

It’s the team that we all know,

It’s the team that we call Liv-er-pool

And to glory we will go.

We’ve won the league, we’ve won the cup,

And we’ve been to Europe too,

And we played the Toffees for a laugh,

And left them feeling blue,

Five-nil!’

And there, we reclaimed the night.

The songs mean so much. All the shared knowledge and belief is most succinctly expressed in the chants, especially the long, convoluted epic that we sang that night.

Over the years we’ve spent more time discussing this song than any other. Does the line about king and country endorse patriotism? Or does the next line undermine it with sly humour? Should he be in a Highland Division? Is it Arabian Sun? Well, it was probably radiant originally but Arabian is established by usage.

On trains, coming back from games, we’ve thrashed out significance and interpretations. It means something.

At the League Cup final against Chelsea, when it reached the ‘shot by an old Nazi gun’ line, a young lad standing near me added the words ‘up the bum’. He was nearly throttled for his disrespect and will not make such a mistake again. It enraged me.

‘What are you, a Manc, an Evertonian?’ I asked. ‘Get down the Chelsea end, dickhead…’

I should go on to say we sang our songs until dawn. Instead, mentally shattered, we mooched off to bed after three or four drinks. Al would be on a plane to Australia before noon and we needed some sleep. The train to Bucharest would leave at 10pm and we knew there wouldn’t be much chance to doze with the border crossings. Sometimes you have to wonder whether we put more effort into this football business than the players.

Read Chapter 18: These were the last words he said

Order Far Foreign Land here: Cost £10 UK, £15 Europe, £18 Rest Of World. All including postage

For those interested in the culture of Merseyside, try my non-football novel. Good Guys Lost, an epic of Liverpool life set from the 1960s to the 2010s