Book serialisation: Far Foreign Land, Chapter 12

Istanbul looms ever closer, dealing with bullying border guards in Bulgaria and a period of panic when the Turks confiscate the match tickets in the middle of the night

Coming up the hill

IT’S GETTING NEAR the end of extra time. The mental anguish of two hours is reaching its climax.

We’ve hit emotional depths, been lifted to unimagined heights and… fallen back on stock phrases. The game we have witnessed has scrambled coherent thought and everyone seems to be communicating in the formulaic phrases of the game.

‘It’s all about heart now,’ one man said to no one. ‘It’s who wants it most’.

Some don’t even speak, just cram their fists into their mouths and gnaw, knowing that in 10 minutes it will all be over. The final whistle sounds and someone says: ‘It’s a lottery.’

There’s a big rush towards the toilets. ‘Twitchy bum time,’ the king of the cliché says. Indeed.

* * *

As Istanbul got nearer, Dave was increasingly erratic. I sent him to the cash machine to get money on my card while I watched the bags and he came back with a single note. ‘Is that enough?’ I asked, knowing that we needed provisions for the journey.

‘I think so, I got confused,’ he said. ‘We don’t need much, anyway. We’ll never be able to change it back.’

So he went to a mini-supermarket and arrived back looking sheepish, short on beer, cheese and meat. ‘I didn’t think I’d have enough,’ he said, explaining.

‘Well get more money out.’

‘But I’ve made a mistake. The girl gave me this in change.’

He held out a wad of notes. A real wad. Thick and showoffy, like a Chelsea fan’s up north.

‘You’ve got hundreds of quid out on my card! I’ll never be able to change it back! You’re an idiot.’

‘I got confused.’ Not with your own card earlier, I thought. Just mine.

‘Go and get enough food. And get me a beer before you go.’

Bucharest was suddenly proving expensive. I managed to get on to the internet using the laptop and mobile while he was gone and checked the exchange rates. The wad he had left me was worth £16. Keep quiet about that, I thought.

We drank another beer and I kept shaking my head at him. There were others, doing the same, and some obvious expressions of disgust from passers-by.

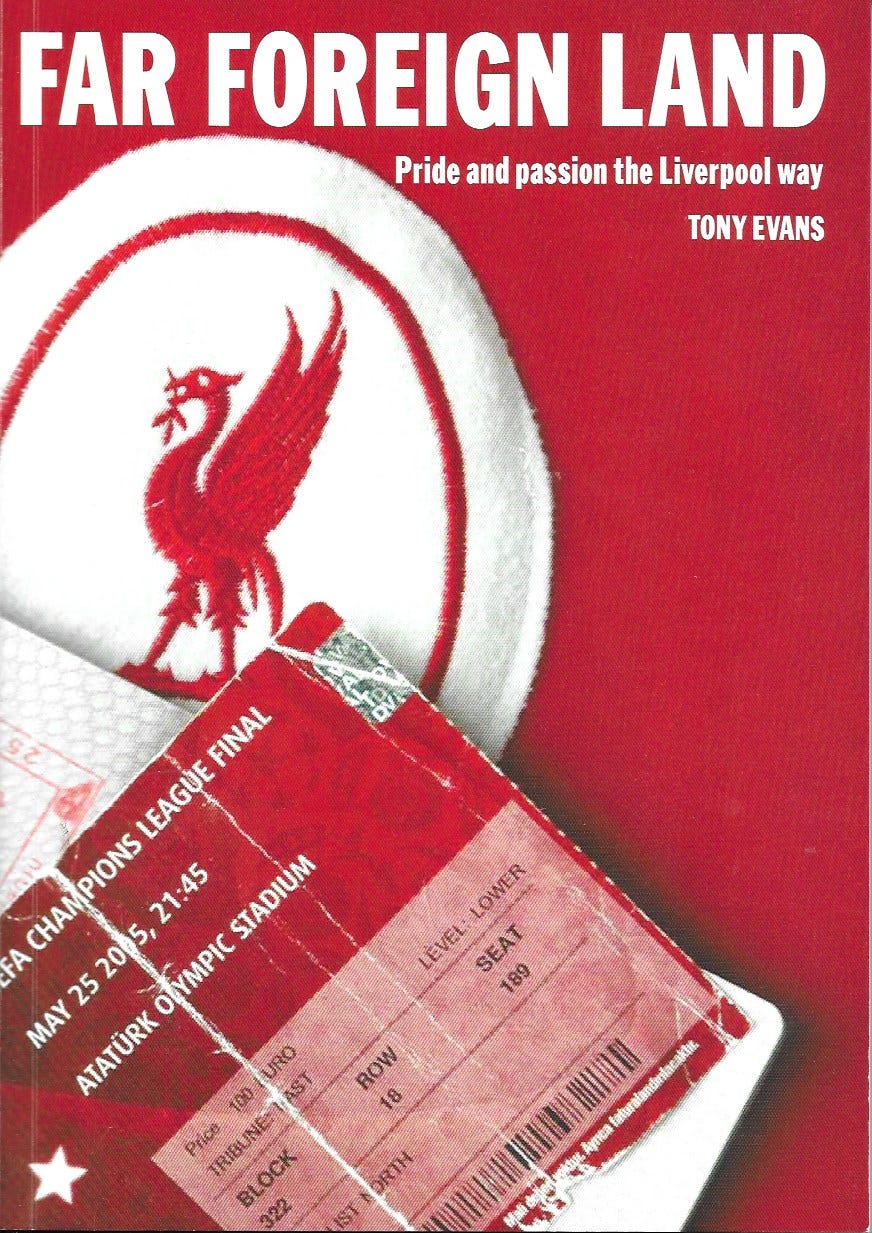

Dave had one hand thrust deep into his hip pocket. It was moving in a way that scares nuns and spinsters. His fingers jiggled around, touching something for comfort - his ticket. It was secreted close to the area of his body that he unconsciously protects most.

A young woman tutted as if he was making some sort of advance, but it was the farthest thing from his mind. He just needed to feel that ticket.

It’s compulsive. So that’s why he’d been sleeping in his jeans.

But Dave’s game of finger-wiggly was tame compared to the vista as the train pulled out of the station. Police were patrolling the trackside for some 400 yards, but after that the sidings deteriorated into a mini shanty town. A man was squatting beside a large cardboard box – the sort a cooker is delivered in – defecating on the ground.

He was gnarled and wiry like an American mountain man and waved at us to look away in aggressive defiance, as if we were peeking through his bathroom window.

We were, I suppose.

It does not take much insight to feel that you are going backwards on the journey from Bucharest through Bulgaria. Every train station looks as if it had been shelled at some point in the previous week and the people appear to have battle fatigue. To them, it must have looked like we were riding in glorious luxury. Even a relatively pampered journey like this puts things in perspective.

Shortly after leaving Bucharest, I visited the bathroom. There was no shower, just two inches of broken cable that spewed cold water when the tap was turned. While the washing area was clean, I squatted under this makeshift shower and felt a pure pleasure from rinsing my body.

The cleanliness didn’t last. Back in the compartment I could feel the sweat pores opening again. They oozed liquid but also picked up the dense flavours of the carriage. Within minutes you suck in the pall of cigarettes and sweat and blend in perfectly with the background like an olfactory chameleon.

The landscape was riven by steep, verdant gorges, sliding down to huge disused factories that look like they were the object of a quarrel between armies in Stalingrad. They ran for hundreds of yards alongside the track.

Where the workers employed here during the Communist era were housed is anyone’s guess. Underground, to judge by the lack of obvious dwelling places. These countries look like they have been plundered over and over again – probably because they have.

A new, vicious round of exploitation appears to be in motion as the state monopolies of the past fracture and find their way into private hands. In the rush to capitalism, no provision seems to have been made for the people of these valleys.

Those who have energy and intelligence will leave, only to be derided as asylum seekers and illegal immigrants when they pitch up in western Europe. The most vocal of their critics are always the first to advise the dispossessed to get on their bikes.

The profits created by the new market economies in the east are always welcome in the cities of the west; their (human) losses no one wants.

The routine of border checks was a welcome distraction, though there is only so far a bleeding heart can go. The Bulgarian passport inspector appeared with an armful of Liverpool memorabilia. ‘You English? Go to Istanbul?’ he asked menacingly. ‘You give me something for my son. You rich. We poor. I want something.’

This was delivered in enough of a Slavic growl to suggest quite a bit of the sweat that infuses these carriages was delivered cold. Here, though, he had picked the wrong pair.

‘Got nothin’, mate.’

‘You give,’ he threatened

‘You piss off.’ And he did. It was easy to see how this man supplemented his income with a little bullying.

We slept fitfully until the three-hour saga that is entering Turkey began. The Bulgarians here were not acquisitive, but it was three in the morning, so perhaps it was hard for them to summon the energy.

Across the border at Svilengrad, they did not expend any. For the first time we had to get off the train and take our passports to the Turks. ‘Midnight Express,’ Dave said as we climbed across the tracks and joined a long queue. There were another half-dozen Liverpool supporters waiting nervously. Some tried to show camaraderie, but it was a tense atmosphere. The pressure rose considerably when a very grumpy official demanded that we stand against a wall and shouted: ‘I want tickets.’

And it was clear that he did not mean a Balkan five-day railpass. I felt like saying: ‘So do I, you officious tosspot.’

Slowly, nervously, the precious tickets were produced. The Turk collected and stacked them, leaving them sitting on a counter while the rest of the passengers were dealt with. There was nervous laughter and then a gasp. The official picked up the pile and disappeared into another room with the match tickets.

Dave had to bite his tongue, which, given the Midnight Express thoughtline he’d been ploughing, should have come as a relief for the border guard. He looked ready to explode ... until the passport and ticket reappeared. The price of the visa to enter Turkey was included in the match ticket and a special stamp was required. However, Dave would gladly pay the £10 entry fee to put the years back on his life.

‘I nearly lost it when he went with the ticket,’ he said as we got back on the train to wait for customs and the police. ‘And when he came back and called my name, I thought we were going to end up in the Goulash.’

Well, it would have been better than the Gulag, but surely worse than the soup. All we needed to do now was sleep for four hours and we would be in Istanbul.

Read Chapter 13: To glory we will go

Order Far Foreign Land here: Cost £10 UK, £15 Europe, £18 Rest Of World. All including postage

For those interested in the culture of Merseyside, try my non-football novel. Good Guys Lost, an epic of Liverpool life set from the 1960s to the 2010s