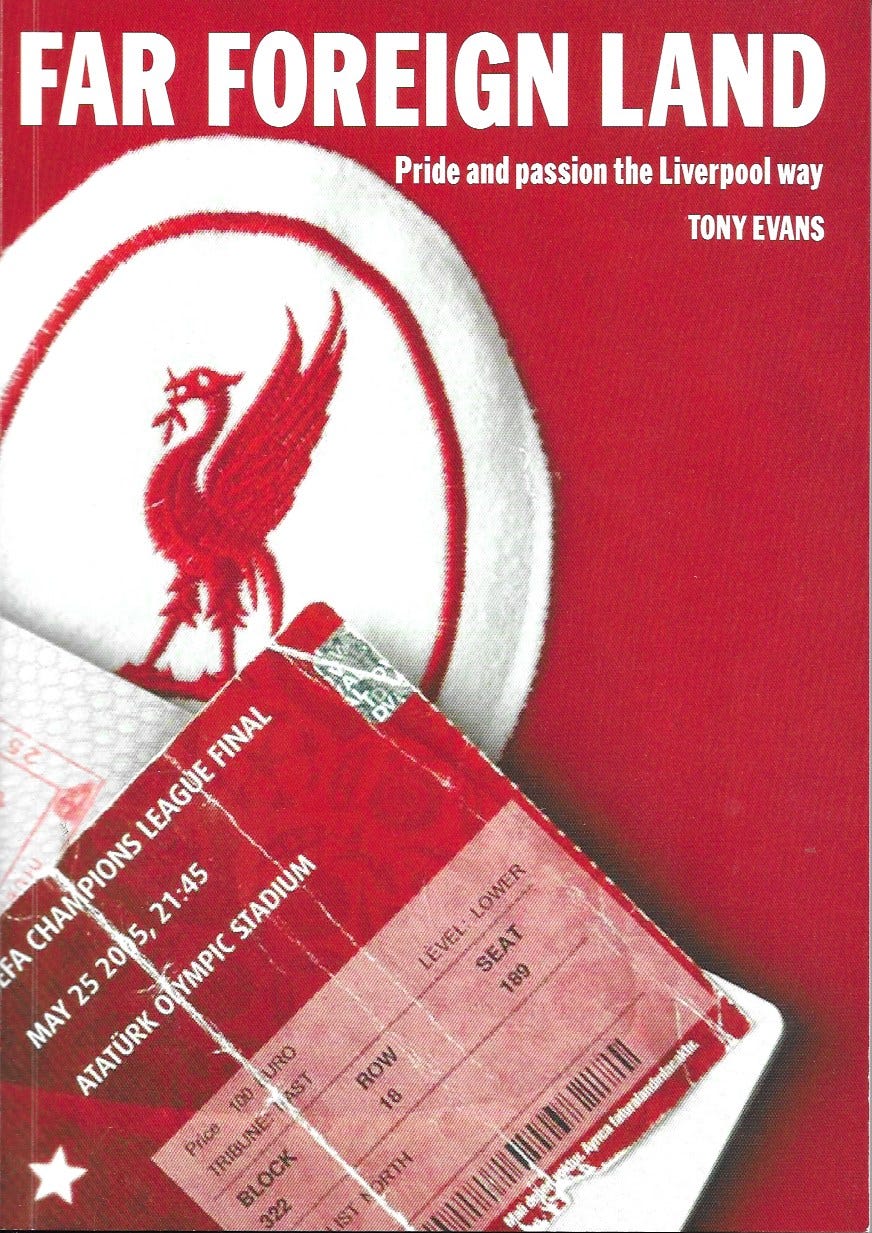

Book serialisation: Far Foreign Land, Chapter 10

A day in Bucharest paying homage to Hagi, the value of travelling with a ball and playing on the pitch where Rush put Dinamo to the sword in 1984

And we’ve been to Europe, too

RELATIVITY HAD BEEN suspended. Three goals, but how long to go?

The scoreboard and the watch suggested that Liverpool had drawn level in just six minutes. It couldn’t be right. Surely it was more like 25? A text came through: ‘The best six minutes of my life.’

Then the reverse side of the equation took effect. As the team took stock and realised the improbability of what they’d achieved, a fear began to creep in that it could be lost so easily. So, instead of pressing home their advantage, they slowed the pace.

Time began to drag. The next half hour crawled, clearly taking in the missing 20 from earlier on.

* * *

‘Thank God we weren’t in Bert Trautmann class,’Dave, rubbing his neck on a grim and rainy Bucharest platform, said. Lack of sleep had made us tetchy and this was not a welcoming environment at 7.30 on a Sunday morning. The only place open was McDonald’s. The journey was beginning to feel onerous.

After confirming a place on the 2.30 express to Istanbul, we considered our options. A wash would be nice and a stroll around the city. We had to live without the wash.

Outside the station we were approached by a taxi tout, who clearly believed that we were Americans. ‘Yankee, I give you tour,’ he said. ‘What do you reckon?’

‘He seems to know the Yankee. Well, never been kidnapped before. Let’s give it a try.’

So into the back of a taxi we climbed, with a sullen and brutish driver and our ratlike little tout acting as tour guide. ‘You give me €100,’ he said.

‘You show us a good time,’ I countered. ‘That could be taken the wrong way,’ I warned Dave.

But he did.

It was a slow start, though.

Nicolae Ceausescu set the agenda. The first stop was the dictator’s masterpiece, Casa Poporului, the People’s House, a building only the Pentagon can outdo for size.

The men had a curious mixture of pride and disgust for Ceausescu. ‘He rebuild city,’ the tout said. We went to two of Ceausescu’s palaces, the graveyard where he is buried – or was it his family, we weren’t sure – then the boulevard where the revolution started

‘Was it better when he was in power?’ Dave asked.

‘I had job,’ the tout replied, flatly, so we were none the wiser.

The men argued for a while, forgetting the tour, as we passed down wide boulevards and crossed huge squares that made us feel like we were in Paris. We passed a cemetery, where coffin makers had set up beside the road and were pitching for business, waving down passers-by and sizing them up with a tape measure. It was interesting and quite a laugh, but this pair were coming up well short of €100.

We arrived outside a graveyard for Italian soldiers who died in the Second World War. ‘Your point, sir?’ Dave asked, very formally.

‘Nah, mate, not interested, we were on the other side,’ I chimed in.

And as if in response to this, the tout said: ‘You understand, Ceausescu very bad. But things not like now. Good to kill Ceausescu but things change for bad…’

We had thought it was funny to act like Americans and wave big notes in front of men like this, but now we felt uncomfortable.

‘Yankees no understand.’

Too true. The complex relationship between people and their Governments, whether radical or based on patronage, communist or capitalist, takes more than a taxi ride to assess. Even in the half-hour we’d been with these men, their sense of loss was compelling. Yet they were reluctant to wish for the old days. And when the morning looked like stalling, Dave had a stroke of genius. He passed the ball the way he was facing.

‘Gheorghe Hagi,’ he said. There was a moment of silence, uncomprehending. Or maybe they thought that their former dictator was the most famous Romanian on the planet. They were wrong.

‘Hagi!’ he shouted. It got their attention. They repeated the great man’s name, pronouncing it in the correct manner, nodding at each other and smiling.

Victoriei Square had become a sideshow. At last we were talking the same language. Next stop was Steaua Bucharest’s stadium. The tout said:

‘Armed guards. For €30 I bribe.’

But we’d already gone, up the stairs, into the stands and, with no one around, dashed for the pitch. Our tout followed us. ‘Champions of Europe,’ he said.

‘Only ’cos we were banned,’ we both shot back. Steaua won the tournament in 1986, the year after Heysel. ‘We’re Liverpool. Going to Istanbul.’ He did not seem to understand, so he shrugged and left us Yankees to our own amusement.

Actually, the stadium was a little like an American High School arena at first sight, with its new, multicoloured seats. However, the crumbling stairways spoke of neglect. The nets were still up and we both cursed our stupidity. We didn’t have a ball.

It’s always a serious error not to bring a ball. It is one of the fundamental items a traveller must carry. You never know on your journey through life when you’ll get the chance to have a kickabout in a world famous stadium.

However, it was enough to be there. We were giddy with excitement.

When we got back to the station, we did indeed pay like Americans. The tout tried to intimidate more cash out of us but backed off when we showed no fear. The morning had turned out wonderfully after all.

Yet there was one thing that bothered us. The stadium looked very different from the place where Ian Rush scored two in the European Cup semi-final in 1984, even allowing for the filter of television. And then we realised that we’d been to the wrong stadium. It was Dinamo 21 years before, not Steaua. There was only one thing for it. Another cab.

And this time we made sure we had a ball.

Dinamo’s stadium appeared from the outside to be even more ramshackle than Steaua’s but with better statues. They are entirely in keeping with a Scouse view of art – muscular Soviet realism. Bill Shankly would have looked upon them with satisfaction.

The statue is Ivan Patzaichin, a canoeist who won seven Olympic medals. Dinamo is a multi-sport club

It got better inside. It was set in parkland and below ground level. The bowl was sunk into the grass and trees. It was hard to see how they could limit entrance to people with tickets. What appeared to be two players were doing fitness tests on a wide v-shaped bank of stairs behind the goal that narrowed down to the pitch. The tunnel looked like a shed and who could imagine what the dressing-rooms were like? But it was hard to care when you could go down to the end where Rushie scored and slot the ball into the empty net.

It was a glorious feeling. Imagine walking up to Anfield or Goodison and sloping on to the pitch for a quick game of cross and head. It was even raining, just as it was in 1984.

Statue of Cătălin Hîldan, who died of a heart attack during a friendly in 2000

Overlooking Dinamo’s ground are a host of tower blocks, like every young man’s fantasy apartments. Open the window and you have the best seat in the house, free. Some of the blocks even have balconies and here is no roof on the stadium to interrupt the view. At Stamford

Bridge they’d call these high-rises a pretentious Italian name, make you have a really crap meal and charge you six grand to watch the match.

In the club shop they had a blood-red retro Dinamo shirt in extra large. It was impossible to resist, with its pair of hunting wolves on the badge and the team name on the back. It cost less than the two cheeseburgers we’d had for breakfast and was considerably more tasteful.

By the time we returned to the station, it was abuzz with people. We discussed whether we had time to get to another stadium in the city, the home to Rapid, but decided the risk of missing the train was significant if we attempted the visit. And then Dave said, in a distracted voice: ‘This is the arse end of the world.’

Eh?

‘No, I mean it in the nicest possible way. Just look at the girls.’

And he was right. Even as humble a star as Kylie Minogue would throw a hissy-fit here, as her rear-of-the-year would come somewhere near the bottom of a best-in-Bucharest table. Yet there was something disturbing about the women.

The well groomed and extremely pretty girls were very young; the older women were universally pug-ugly.

There was no in-between and little sign of attractive women in their 30s. Either middle age has an horrible effect on Romanians, or all the pretty ones leave and take their chances in the wealthier cities of the West. You don’t notice the men so much but the reasons for this are

obvious.

The bright, the beautiful and the motivated up sticks in a place like this. A city that turns people into taxi touts drives away the most capable and vital of its inhabitants.

I’d seen this happen. I’d been here before, some 1,500 miles to the west, on a bay off the Irish Sea. Clearly, we hadn’t come so far.

Read Chapter 11: The battle it started next morning

Order Far Foreign Land here: Cost £10 UK, £15 Europe, £18 Rest Of World. All including postage

For those interested in the culture of Merseyside, try my non-football novel. Good Guys Lost, an epic of Liverpool life set from the 1960s to the 2010s