Football, Fathers And Division

There's been a lot of fine writing about dads and sons bonding at the match but, 50 years on from my father's death, it's clear the game drove us further apart

FIFTY YEARS AGO on the last day of January, the phone rang at 5.30am in the morning. There could only be one reason for the call. My father was about to die.

My first thought was simple. No school for me today.

There was a hushed rush and then my mother left the flat in Burlington Street where my two aunts lived. An hour or so later, the telephone rang again. It was over.

No one said anything. In January 1975, a lot of things went unsaid.

I’d found out that he was going to die on the previous Sunday night. My mother, thinking I was asleep, was on a call to someone. She said: “The drugs will shorten his time but he won’t be in so much pain.”

When she hung up, I followed her into the living room. I asked: “Is he going to die?”

She just looked away. Her two sisters sat in silence. After waiting a moment, I went back to bed. I was 14.

What kind of man was he? I can’t really answer that. He was in my life for such a short period. For my first seven years, he was a fleeting presence, showing up on the doorstep of my auntie’s flat where we lived. He was never invited in.

Then, when I was seven – a brother had arrived, unheralded, a couple of years earlier and a sister was on the way – he picked us up in a car and took us to Fountains Road. We entered a ramshackle terraced house with an outside toilet. This was our new home. A family home.

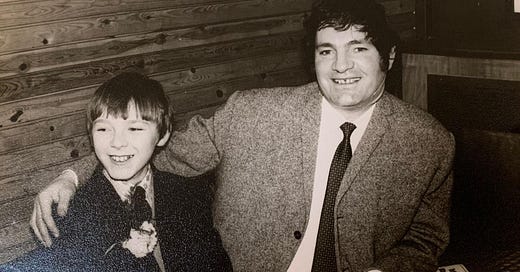

Me and Jimmy at a wedding

This was jarring. It was less than two miles away from where I’d grown up but a very different place. The first thing I noticed was that in the lunettes above the front doors there was either a photograph of the Queen or a representation of William of Orange on his white charger. Ours had the Sacred Heart. I’d barely heard the term ‘Protestant.’ We called them ‘King Billies.’ I knew from the start I wasn’t fitting in round here.

On the plus side, if you walked 100 yards to the top of the street on to Walton Lane, the entrance to Stanley Park was across a zebra crossing. You could see Goodison from here.

And the street beside the park was Anfield Road. You could be at the ground in a matter of minutes.

There has been lots of moving writing about how football created bonds between father and sons; how a shared interest in the game allowed expressions of love that might not otherwise have been articulated. Football did the opposite for me and my dad. It placed another barrier in an unbridgeable gap.

You might assume from this that Jimmy Evans was an Evertonian. The opposite is true. He was a Red through and through. He took me to my first games. But, at the earliest opportunity, I made my own way to matches. I did not want to be with him.

So back to the question: what kind of man was he? The answers are superficial, because I never got to know him. He was a bouncer by profession – a doorman, he’d say. There was an aura of violence around him.

Most of what I know about him I heard from others. Some two decades after he died, I was in town with my youngest brother. We saw a couple of my father’s cousins on what appeared to be a night out for aging villains. They spotted us and called us over for a drink. One of their company said: “Your dad was my hero. The first man I saw firing a gun in Liverpool. It was when the Krays came to town. He was popping off down Lime Street…”

In those pre-drugs days, gangsterism wasn’t always lucrative. When he died, Jimmy had £96 in the bank and a 50p piece in his pocket. Not a lot to leave a 37-year-old widow and four children. My mother cherished that coin. Until I took it and bought sweets with it.

I always got the distinct impression that this man who barged his way into my life didn’t like me. It may be hard to believe, but I was a timid child, used to being cossetted by women. He was a fine sportsman – a boxing champion in the army and a very good footballer. When he threw me the ball, it bounced off me. I wasn’t tough, either.

He was only violent to me once. We were getting ready for school and I spoke to my sister, who ignored me – she hadn’t but it would be years before we found out she had hearing problems. I called her a “stupid cow.” Jimmy was shaving in the kitchen and thought it was directed at my mother. I can still recall seeing stars after he slapped me. He kicked me up the first steps of the stairs. It was a disproportionate assault.

I was kept off school and hid in the bedroom. Later, he seemed to realise what he’d done. He came and got me to watch the racing with him. “Let’s pick some horses.” I did it. But only because I felt I had no choice.

Most nights he would get ready for work around 9pm. He would don a dinner jacket and a bow tie. I’ve always associated this sort of dress with doing the doors. On the occasions during my career when I went to black-tie events, I never felt any sense of glamour. Looking in the mirror, I’d never see a suave man-about-town. Just a bouncer. I hated every minute in a uniform I linked with violence.

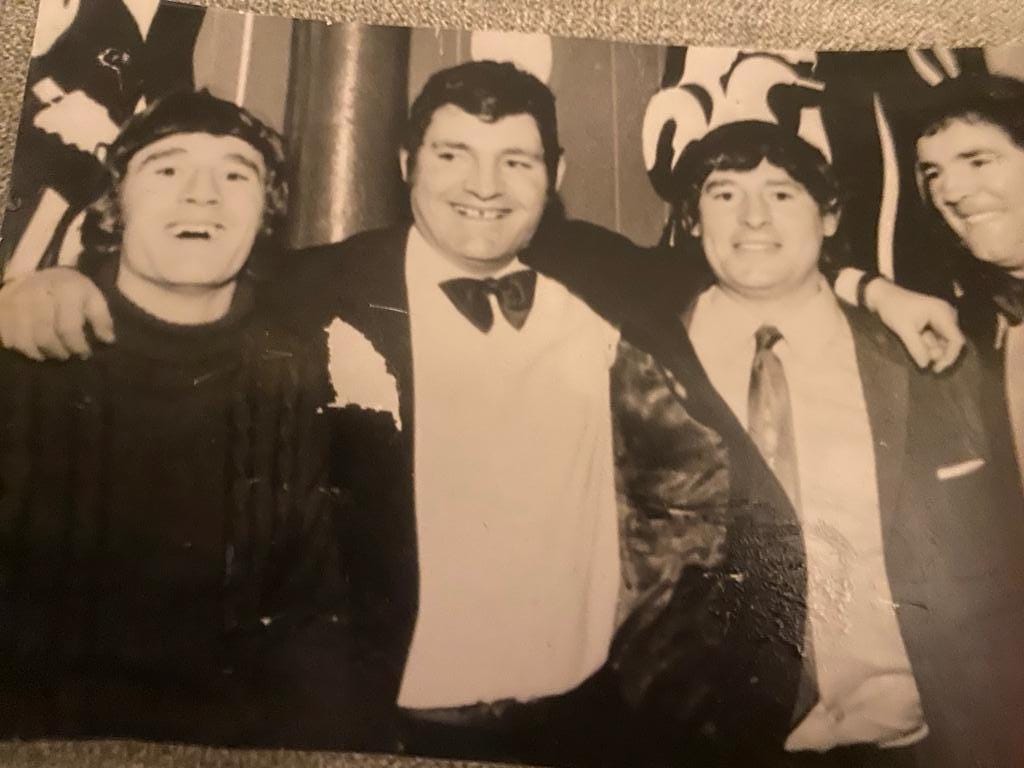

The Evans brothers: Tony, Jimmy, Bobby and Ben

The most obvious thing he thought we had in common was football. But I did not like being with him, even at the match. The kid next door was a year older than me and went with his cousin. I agitated from about the age of nine to go with them. Yeah, you might find it hard to believe in 2024, but boys of this age went to the game unsupervised by adults.

We would leave the house at 12.30, go to one of the nearby shops, buy a sarsaparilla and sweets and be at the Anfield Road gates when they opened at 1pm. We would hang over the fence near the corner flag on the main stand side and be in position until 4.45. The regulars knew Reggie and Ronnie, my companions, and would keep an eye on us when bigger kids tried to nick the spec. They soon got to know me, too.

Meanwhile, my dad was in the main stand – he was always in the obscured view section near the Kop. He wanted me to go with him but I was having none of it. Yes, I’d go to away games with him but that was the only way I could get there. The rift between us grew wider.

In the final two years of his life, he mellowed a little and became more of a family man. We moved again to a new house just off Smith Street. I still tried to spend as much time as possible at my auntie’s place and we continued to go to Anfield separately.

My mother told me he was really looking forward to when I was old enough to go for a pint with him. He definitely wanted a father-son relationship with his oldest child. But it was too late for that by the time he arrived in my life.

Kids are cruel and I was vicious. I was not impressed at finding out about his impending death in such a manner. I refused to go to the hospital to see him in those dreadful four days he remained alive. My mother pleaded with me. “He’s asking for you.”

Nope. I picked up my Wembley Trophy and went down into the block, spending the next couple of hours kicking the ball against a wall. Football was a weapon to use against everyone. I ignored my mother when she left to go to the hospital. She was crying. My hard little heart had no room for compassion.

On that Friday 50 years ago, crammed into that little flat, I told my younger brother that his dad was dead. He cried softly. Neither of us went to school.

Later, we took the ball and went out. Even then, he was such a better player than me. We lost ourselves in the game. As always. Football transcended death.

The next day, there was no Anfield. Liverpool were away at Highbury and lost 2-0 to Arsenal. It would be trite to say I was more upset by the result than the death. But that’s how I think I thought.

I was not going to stay in the flat. Instead, I went to Goodison, where Everton beat Tottenham Hotspur 1-0. What do I remember about that day? That I was impressed by the Spurs away mob. Nothing more.

Jimmy Evans had had a cancerous growth on his neck for years. The doctors thought it had spread and he had lung cancer. It turned out he had asbestosis, contracted in the six weeks he worked in a sacking factory when he was 16. A nurse intimated to my mother that the misdiagnosis and subsequent mistreatment killed him earlier than it should have. He was 41. His three brothers, Bobby, Ben and Tony would also die of cancer at a young age.

There was no chance he would have lived for another 50 years. But he would have appreciated a few more. Would we have bonded if he had not died? Would I be writing about how important matchdays were to us? I doubt it.

Football was a shared obsession that we never shared. That’s the funny thing about the game. It can divide even those on the same side.

Early this morning, about 5.30, I woke and thought I heard a phone ringing. It was the sound of the seventies. Frankly, I was scared.

I thought Jimmy Evans was in the flat. Shaking, I went from room to room, expecting to see a ghost. There was no one there. Sweating, I lay back down.

Then I realised he was there. In me. I see him in my reflection. I'm the ghost.

You can go the match separately, but genetics tie you together forever. Like it or not.