The (Liverpool) Boys In The Band

Not many music careers start in the away end at Old Trafford. Here's the story of how I joined The Farm

Most how-did-you-join-the-band stories feature ads in the music press, nightclubs or gigs. Mine, characteristically, took place in the scoreboard end at Old Trafford.

It was February 26, 1983, Manchester’s turn to host the festival of hate that was United versus Liverpool. These fixtures were always hostile. David Lacey, in The Guardian, wrote that the Stretford End that day created an atmosphere of “savage passion reminiscent of the games immediately after the Munich air crash and, later, the years of Law, Best and Charlton.”

There were certainly mentions of the disaster from our end: I recall someone threw an inflatable airplane into the no-man’s land between us and the paddock. Once again, I look back in horror at what the great Bobby Charlton must have thought of it all.

The only other thing I remember about the day – it was a 1-1 draw, Arnold Murhen scoring after 36 minutes and Kenny Dalglish equalising before half-time – was a conversation before the match. Among our group was George Maher, who I’d met at university. He had played trumpet in the Liverpool Schools Orchestra. He was approached by Peter Hooton.

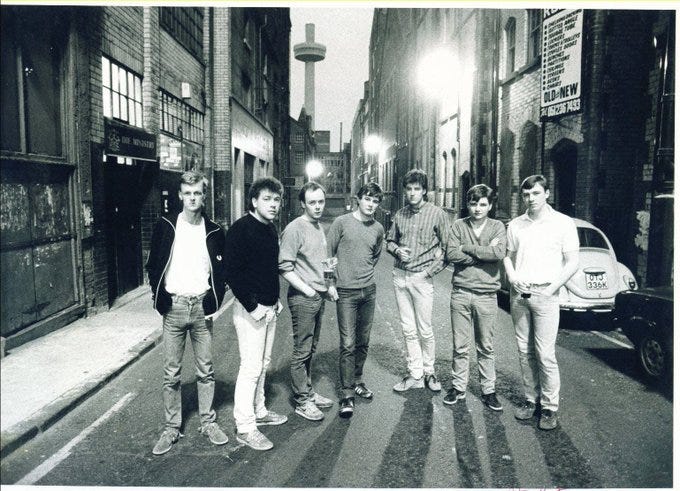

The Farm outside the Ministry rehearsal rooms. And the Wine Lodge

I knew of Peter as one of the creators of The End, the brilliantly innovative music/football/style/politics crossover fanzine. He frequented the American Bar, known as the legendary Yankee to Liverpool boys, a place where I was a regular.

Hooto addressed George. “I hear you play the trumpet. You fancy seeing what it sounds like with the band.” The Farm were beginning to build a following and they rehearsed in the printing facility operated by George’s dad where The End was produced.

My mate was enthusiastic and agreed. Then he pointed at me. “He plays, too. We’re a section. He’ll come along.”

Maybe this is why I don’t remember much of the game. I was in shock. Saying I played was stretching the truth. I was still on Tune A Day book one.

George went to Anfield Comp, which had an excellent music department. My school was a mile up the road, Cardinal Godfrey. Music was on the curriculum and there was a piano in one of the rooms, the only instrument on site. The lessons consisted of Mr Ingham, the woodwork teacher, bashing out Men of Harlech and other martial songs for 40 minutes while we sang along tunelessly.

Incidentally, on our first day at senior school, Ingham addressed the new boys. “I’ve got the best selection of bottomsmackers in the north west,” he shouted across the silent yard. “Ask the bigger boys with broader bottoms.” He did, too. Mahogany, oak, beech, walnut. The man loved his hard woods and spanking boys. But I digress.

I got suspended from university for a year and decided to make good use of that time by learning an instrument. George had a spare trumpet. I borrowed it and was taking a half-arsed approach to practise. Forty minutes before kick-off at Old Trafford I found out I was in a brass section.

The next day we convened on Cases Street, played for a bit – George kept the trumpet parts very simple – and legged across the street to Coopers as soon as it opened. By then I was in a band. It had been a strange 36 hours.

Things got weirder at a rapid pace. Our first gig was some time in March at the long-gone Masonic pub on Berry Street. It was, if memory serves, a Tuesday night. Apart from those accompanying the band, there were about six punters. Things seemed to go OK. A week or two later Peter rang. “We’ve got another gig.” Sound. Where? “The Empire. Supporting the Style Council. Their first gig. The first of May.”

Surreal.

Walking home from the soundcheck at the Empire across the waste ground between Fontenoy Gardens and Leeds Street, the absurdity of it all struck me. I sat down in the grass and laughed. The words of Mott The Hoople’s All The Way From Memphis were going through my mind. “It’s a mighty long way down rock’n’roll, from the Liverpool docks to the Hollywood Bowl, and you look like a star but you’re still on the dole…” They were not quite in the right order but you get the picture.

Hooto and I were into football, as was Kevin Sampson, the manager. Sammo went on to write Awaydays, the best fictionalised hooligan book (and most supposedly real-life hooligan books as pure fiction).

There was little crossover between musicians and matchgoers at the time. Prospective pop starts were mostly too cool to be interested in such a vulgar pastime. Those who were into the game and made a big thing of it were a little cringeworthy: Rod Stewart, Elton John and the Cockney Rejects come to mind.

But Scally culture was an integral part of The Farm’s persona. It wasn’t an affectation. That was just the way we were. One A&R man quipped: “Where did you get your image? Borstal?”

Football started it but it also got in the way. In 1984, I missed rehearsals claiming I’d split my lip and couldn’t play. The excuse would have worked if I hadn’t bumped into Sammo in the away end at Walsall for the second leg of the League Cup semi final and got a ticking off from the manager.

We played London the day of the FA Cup semi against Southampton at White Hart Lane – we often tried to play venues that coincided with Liverpool away games – and I fell off stage. The general presumption was that I was drunk. Well, I might have been. But I was also severely concussed after Southampton fans kicked me round the High Road and attempted to throw me through a shop window. Our boys were expecting a fairly chill semi final, forgetting that Everton had given Saints fans a spanking at Highbury two years earlier. They wanted Scouse blood, red or blue.

Bands almost always fall out and split. It eventually it happened to us. By then I was playing the trombone – an instrument that suited me much more – and we’d put out a clutch of singles. The band’s sound was quite different to the style people are familiar with – their new single Feel The Love is a classic Farm anthem – and someone described it as a mix of Dexy’s meets the Undertones. When the split came, I put my friendship with George, who died last year, first even though he was in the wrong. We played together for a couple of years and Peter and the boys went on to global success with Groovy Train and Altogether Now, both classic singles.

Football still bound us, though. Hooto and I found ourselves listed as prominent figures on the infamous Khmer Rouge blacklist produced by Liverpool in the waning days of the Gillett & Hicks regime.

The moral of the story? If you’re at the match and you get railroaded into joining a band, embrace it, even if you can hardly play. You might have a good time. I did.