'There Has Never Been A Better Time To Be Poor'

So begins Good Guys Lost, an epic novel of Liverpool life over six decades. Music, murder, mayhem, gangsters. In the opening section, meet Billy an optimistic teenager in 1965

Part One: Charisma

“There has never been a better time to be poor,” the youth said, catching the attention of the group of boys sitting and squatting around him. They stopped playing cards for a moment – pontoon, to allow as many participants as possible – and listened. Silence in such a gathering was unusual. They waited, the spitting and swearing held back as nine teenagers found themselves tuned in on the same wavelength.

Billy paused just long enough, almost too long so that the tension nearly broke. When he did speak again there was a surge of belief in his voice, the tone that captures an audience. Two flights above, in an identical concrete stairwell that the sun never reached, a four-year-old felt the thrill of the words as much as the group below. It was the first time the child had consciously experienced charisma and, like the youths downstairs, he was captivated.

“There has never been a better time to be young and working class. For the first time, we have money in our pockets. The world knows who we are. Everyone wants to talk like us. Our accents open doors. We can do exactly what we want and we don’t have to be like our mams and dads.”

Somewhere in those six sentences, the charisma went awry. By the time Billy spoke of parents, his mates had begun to snort, curse and deal the cards. The authentic conviction of his opening gambit drifted away and now he was just another kid fighting to make his voice heard over the flippant clamour.

If you don’t want to wait for the next extracts, the paperback is available here

The upsurge in swearing grew louder as Mrs Ashton, who lived adjacent to the stairs on the first landing of this tenement block, appeared with a bucket of water and flushed the group out of the gloom and into the sun. They laughed and jeered – at each other and not, directly, at their neighbour – and mooched off to find another block to lay out their cigarettes, tanners and cards. There were plenty around in the flats that ran in long lines between Vauxhall and Scotland Roads, spewing out the meat that fed the factories and docks.

Billy looked back and spotted the boy peering through the railings on the third landing. He winked extravagantly and skipped off at the rear of the little gang, bouncing along with the happy, excitable, threatening strut young men assume in groups.

He was wrong, of course. This was 1965 and the doors that appeared to be ajar to Billy and his friends were illusionary. The accent was no longer opening escape routes. Those who rode The Beatles’ coat-tails had already done so, often with faux versions of the Liverpool dialect.

But his charisma lingered in the air as it does when it leaves an imprint, however fleeting its presence. The young boy sat on the stairs and savoured its feeling, repeating the words and trying to feed in the crackle of relevance without any success. “There has never been a better time to be poor,” the child said. “Never.”

The eavesdropping boy was me, of course. I realise, when I look back, that this was the instant that I became properly sentient and started to become aware of the world. There were earlier memories but they were a tableaux of fleeting significance with little substance.

I had not thought about being poor before that moment. After this, it began to become clear what it meant. It was the day I joined the great war against patronage, the crusade against vulgarism. Or am I recounting history backwards?

Things are so different now, so much change has occurred, that I do not recognise that child. He lived in a different world to the one I now inhabit. I can only recall his story as if it happened to someone else. His growth into adulthood and the struggles that came along the way feel like a tale told to me by someone else, someone I distrust. The dismantling of the fabric of his society somehow broke the narrative chain between me and him.

Perhaps none of the subsequent battles involved me at all. So why am I so certain I was on the losing side?

*

Billy’s story is easier to tell but it throws up many questions. Some are difficult to answer. It is best to start with the hardest.

What generates charisma? What separates one man from another and allows a politician or entertainer to stand before an audience and immediately, instinctively, grasp their attention? What is it that speaks and spells coruscating brilliance to the world?

Billy had it. Sometimes. Where did it come from? It is much more simple to explain where he came from.

He was born on a January night in 1950, making his grand entrance with an unexpected, though typical, flourish. His mother, Lilly, still had a month to go and grow when she sat on a misplaced knitting needle. The unexpected enema forced a sudden and premature labour. There was barely time for the midwife to arrive before a squalling boy popped out, born at home in Burlington Street and none the less healthy for it.

Billy caused a fuss right from the start. Few households would be so divided by a choice of name. Mickey, Lilly’s husband, was away at sea at the time of birth. He was still a week from port when the needle precipitated his son’s early entrance.

The new father was outraged when presented with little William. He was expecting a boy to be given the names James Larkin, in homage to the great labour leader and republican. That honour would have to wait for his second son, two years later. His wife used Mickey’s absence to register the child with a forename of her choice.

It was not a simple matter of taste that enraged her husband. William was just another name across most of England but on the Celtic fringe – and in the tenements of Liverpool’s Catholic North End – it was imbued with politics, triumphalism and humiliation.

Billy’s mother had grown up a mile inland, on the Protestant slopes of Everton Brow. It was a parallel, orange-tinted universe to the dockside community in which she gave birth.

In the terraced houses off Netherfield Road, fidelity to the crown was instinctive and William of Orange a symbol of Protestant domination. The loyalty of the residents was unshakeable. The fanlight windows above the front doors were often decorated with either crude depictions of King Billy on his white charger at the battle of the Boyne or beautifully composed photographs of George VI displaying sombre regality. Respect for the monarchy was ingrained on Everton’s heights.

From the scrubbed steps of their terraced houses, the Protestant occupants could look down the steep streets all the way to the Mersey and beyond. What they saw was alien territory. The demarcation line was clear. England as they knew it ended at Great Homer Street, the home to the ragged bazaar known as Paddy’s Market, a place where the North End’s poorest shopped.

Three hundred yards west of the market was St Anthony’s church, perched on Scotland Road like a beacon for the disposed. Squeezed between here and the river were the cramped, pinched tenements where Catholics lived, an area still rife with rancid courts and leaky cellar dwellings. More than a century had passed since the Famine but the folk memory of division persisted. Lilly’s childhood Protestant neighbours despised “the Irish” of the docklands. The Papists refused to assimilate and produced throngs of feral children, they told each other. Her father was in the Orange Lodge and proud of his staunchness.

Marrying someone from the other side of the religious divide was still anathema in the 1940s but Lilly crossed the line for love. It could have been a dangerous adventure.

The sectarian riots that Lilly’s parents remembered in the early part of the century were largely a thing of the past but there were enough flashpoints during the marching season to make life uncomfortable for interlopers in the other community. Lilly moved into an area that was overwhelmingly Catholic and republican. It had sent an Irish Nationalist MP to Westminster less than two decades before she married Mickey. Down in Liverpool 3 even the most meagre slums were decorated with pictures of Popes. No one wore orange.

She would never deny her background, though. Billy might have been born under the gaze of a pontiff but his mother used him to assert her identity.

So, it was with a certain amount of satisfaction that Lilly watched the Irish parish priest scowl at young William’s name over the baptism font. You do not have to be a bigot to enjoy annoying priests – or husbands, for that matter.

For all that, Billy grew up in a happy home. In the tight-knit tenements, Lilly could have been seen as an outsider – especially with a husband away at sea for long periods. But, right from the start, she embraced the complex network of insular, extended family relationships that characterise ghetto life. She had a forthright honesty that defied exclusion. People liked her. She had something about her.

It would have been easy for others to resent the family. By the standards of the neigbourhood they were well off. Mickey was a ‘Cunard Yank,’ a seaman who made the Liverpool-New York run in the summer on the Britannic, leaving the bomb-craters and austerity of a land fit for heroes for cities that were filled with luxuries and pleasure. In an era when few men of any social background knew their wife’s dress size, Mickey and his friends would shop for their womenfolk in Macy’s and Bloomingdales, stopping by at Sears and Brooks Brothers for their own suits. When the stores are 3,000 miles away you’d better get the right fit.

They strutted home from the docks carrying bags full of food and clothes, but that was the least of it. Fridges, record players and washing machines were bought cheaply in the second-hand shops of Manhattan, manhandled up the gangplank and, with a little help from the ship’s electrician, made workable – if not safe – on the National Grid.

So Billy, when he wasn’t clambering over the adventure playgrounds the Luftwaffe had created, stealing lead and committing the casual vandalism that comes natural to young boys, came home to clothes and toys that his schoolfriends could only dream about. “They dress him like a little prince,” the old women would say admiringly after church on Sunday.

Then there was the music. Mickey’s younger shipmates, sharp in kid mohair suits and Tony Curtis haircuts, would bring home records fresh from Birdland or the Metronome. They blared out of the tenements, echoing across the concrete valleys and bouncing off factory walls.

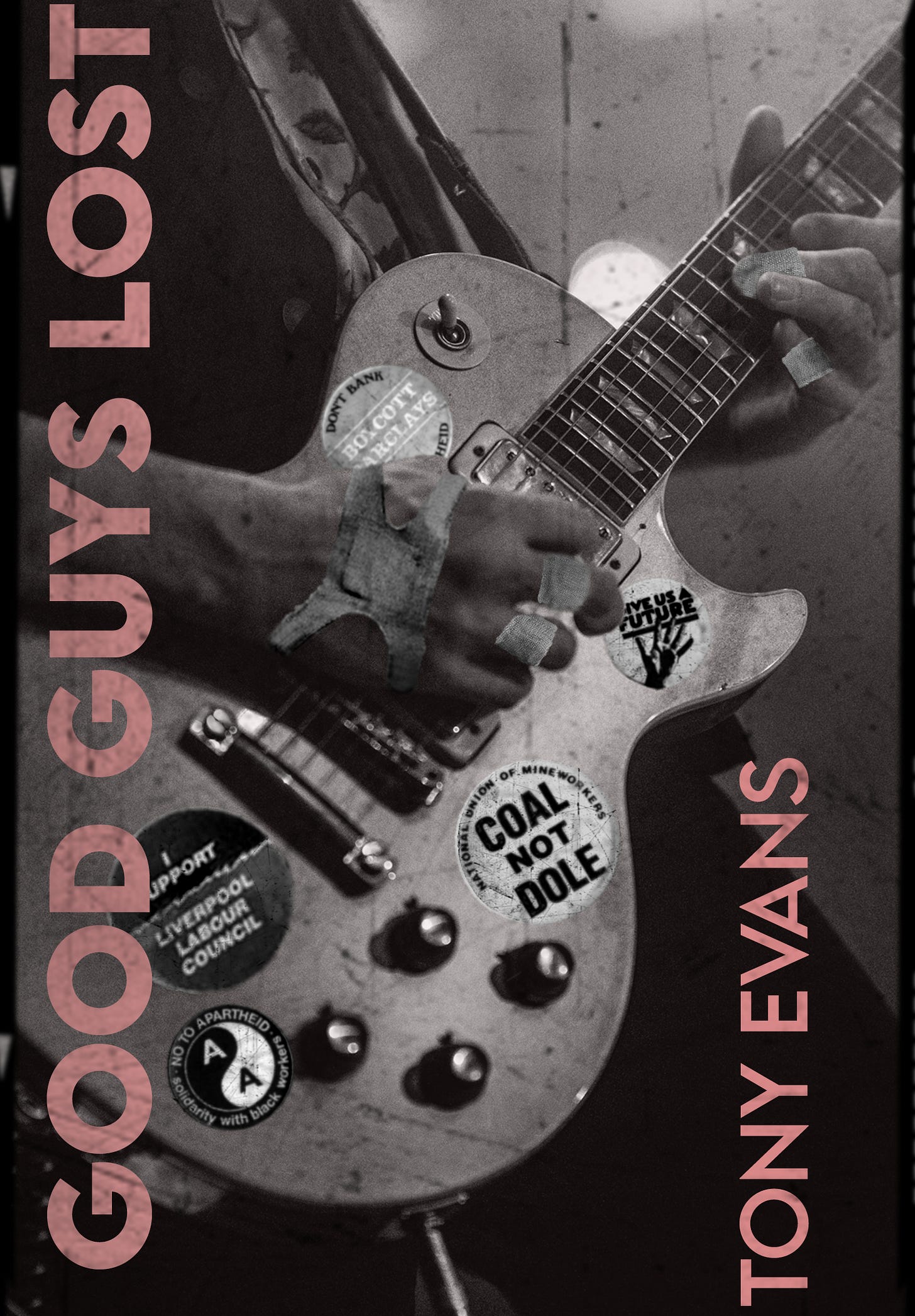

The young bucks bought instruments, too, imagining that in their idle hours in the cabins they would learn to play and – maybe – one day make recordings themselves. It was from one such dreamer who had quickly grown bored with his instrument that Mickey bought a Gretsch semi acoustic guitar for his eldest son. For a couple of years it lay unused in the flat, being of little interest to Billy. Then, when he was ten, he picked it up and studied it with intent for the first time. Rock ‘n’ roll had arrived. Times had changed. He’d never had it so good.

*

The guitar, for so long stringless and unloved, took over Billy’s life. The pads of his fingers hurt at first but he persisted and developed the ability to strum and fingerpick a tune. Instinctively, his brain was able to unravel the mathematical formulae behind a variety of songs and recompute them for a voice more suited to the sea shanty. The sound was plaintive, nasal and cheaply moving. It could hold an audience, however briefly, to silence. It granted Billy charisma.

He began to entertain. Initially it was just family and friends who came together after Sunday dinner, bottles of Mackesen cracked for women, whiskey poured for men primed by the pub for a singalong. Billy would roughly duplicate the hits of the day – Smoke Gets In Your Eyes, Cathy’s Clown – earning coos and generous nods.

Capturing the audience and keeping it were different problems. The diet of chart toppers soon lost the wavering attention. This was family activity, not a concert. Everyone wanted to sing. What Do You Want To Make Those Eyes At Me For? would get things going but, invariably, he was forced to play the ‘old songs,’ even though they were of no great vintage: If You’re Irish, Come Into My Parlour and Come Round Any Old Time.

On Sundays, with the reek of carrot and turnip and cabbage still lingering after a robust dinner, a dozen or more people would cram into the tiny living room and talk, smoke, drink and sing. At teatime two white, square boxes of cakes and jelly cremes from Sayers were produced. The young minstrel was well rewarded with treats as well as thrippeny bits, tanners and shillings.

When Billy was 13 the Sunday afternoon venue changed. He started taking his guitar to the parish club after the lock in. He would be indulged a song or two of his own choice and half a bitter before drink gave his neighbours voice. Then, he would strum Your Cheating Heart while a local woman poured what feelings she had left after producing half a dozen or more children into a wobbly yodel that encapsulated the pub-singer’s pain. The drinkers loved country and western, the descendent of rhythms that had, like these people, left Ireland in time of famine. The music had journeyed on to the Americas, to be made richer and more powerful, and had returned to touch the lives of the fellow travellers who had been beached in Liverpool. Soon the songs of the stranded were to sweep the world but no one could imagine that when Billy initially took to the stage. Soon, though, he was adding Beatles’ tunes to his repertoire and dreaming that he could follow in their footsteps. For the time being he had to be content to duet with drunks, dream of Nashville and show off his beer breath to his mates as they shuffled along to six o’clock mass.

*

One Sunday afternoon, after he had been entertaining drinkers in the big club, Billy was packing up his guitar when a woman called him over to her table.

“You were good, lad,” she said, over a forest of Mackeson bottles. “You should let Sissy tell your fortune. She’ll tell you whether you’re going to be the next Gerry Marsden.”

Billy looked at the women with suspicion. Was he being mocked? But Sissy Campbell, who was in her 30s but could have been nearing double that age, grabbed his wrist and began examining his palm.

“I see a future for you on the stage,” she said with great seriousness. Despite his misgivings, he wanted to know more.

“The Landing Stage!”

The women cackled and Billy felt foolish. ‘The Lanny’ was at the Pier Head, a dock that rose and fell with the tides of the Mersey. It was the world’s first floating platform for servicing ships and a source of civic pride. It was also a site of tragedy.

Billy’s grandfather had been a porter there 30 years earlier, waiting for liners to land so he could earn a pittance by hauling the trunks of the wealthy from the river to the Adelphi Hotel. When he was 31, a seagull pecked him in the eye and the wound became infected. He did not live to see 32.

The crones guffawing around the table knew this – the mesh of tight-knit communities is frequently barbed – but the easy joke could not be resisted.

Trying not to show how severely the malevolent gibe had affected him, the young man took his guitar case, went down the stairs and pushed open the exit. Outside, he breathed in the afternoon air and made a momentous decision. That would be the last time he would entertain for free. He would never again perform merely to give pleasure to an ungrateful audience. If he was to be humiliated after performing in the future, he would be paid for it.

Across Burlington Street, from one of the perverse courtyards that gave Portland Gardens its name, came the sound of boys playing. There was a 30-a-side football match going on and Billy went across and looked over the wall at the mayhem. Jimmy, his brother, spotted him and trotted across.

“Come’ed, Tommy’s waiting,” Jimmy said. “Go pudding and beef.”

If someone turned up and the sides had equal numbers, the newcomer had to remain a spectator until another boy arrived to even up the teams. The pair would confer and decide who would be designated ‘pudding’ or ‘beef.’ The choice would generally be made by the toughest kid in the game – the ‘cock’ of his street or block – who called whichever of the words that came to mind. It was a coin toss for kids who had no coins and made selection random, so that all the best players did not congregate on the same team. But Billy did not want to get involved. “Nah, I’m fed up,” he said. “I feel like a pudding anyway.”

He told his younger brother about the incident in the club. “They’re soft,” Jimmy said dismissively. “Come’ed, play. Tommy’s been wating ages.” The other boy looked on in disappointment. His hopes had been raised by Billy’s arrival but now he went and sat on the wall, frustrated.

Billy was not interested. He went home and sat spreading chords slowly as the twilight deepened.

When darkness fell and the squares were quiet during mass, Billy headed towards church. Sissy Campbell lived on the ground floor of the Bond Street flats and her back windows looked across Eldon Street at Our Lady’s. Billy had not come to pray. He launched a fragment of brick through the woman’s window and scampered through the arch back into Bond Street before the glass had stopped tinkling. He slipped into the deserted stairwell of the next block and sat down, hidden just beyond the first turn in the stairs. “Predict that,” he said before strolling down to Vauxhall Road, where his mates were lurking around the doorway to The Black Dog pub.

Next: “This was a time when gangsters and footballers lived among the communities that bred and revered them.” Meet Duke, Billy’s glamorous hard-man cousin