Book serialisation: Far Foreign Land, Chapter 16

The long, cold walk to the ground and the contrast between Uefa's treatment of corporate fans and the unwashed masses. Plus how Liverpool's banner culture lifted flagging spirits

You’d better hurry up

JON DAHL TOMASSON puts his penalty away and the pressure is on John Arne Riise. He is probably the best striker of the ball in the team. If he scores, only one of the two final Liverpool penalty-takers needs to be successful. It could be an almost unassailable lead.

Riise is hesitant in his run-up and appears to change his mind as he hits the ball. Dida saves. He didn’t blast it. Now we’ve given them a chance.

Victory was so close. So close. Let’s hope there isn’t another twist.

* * *

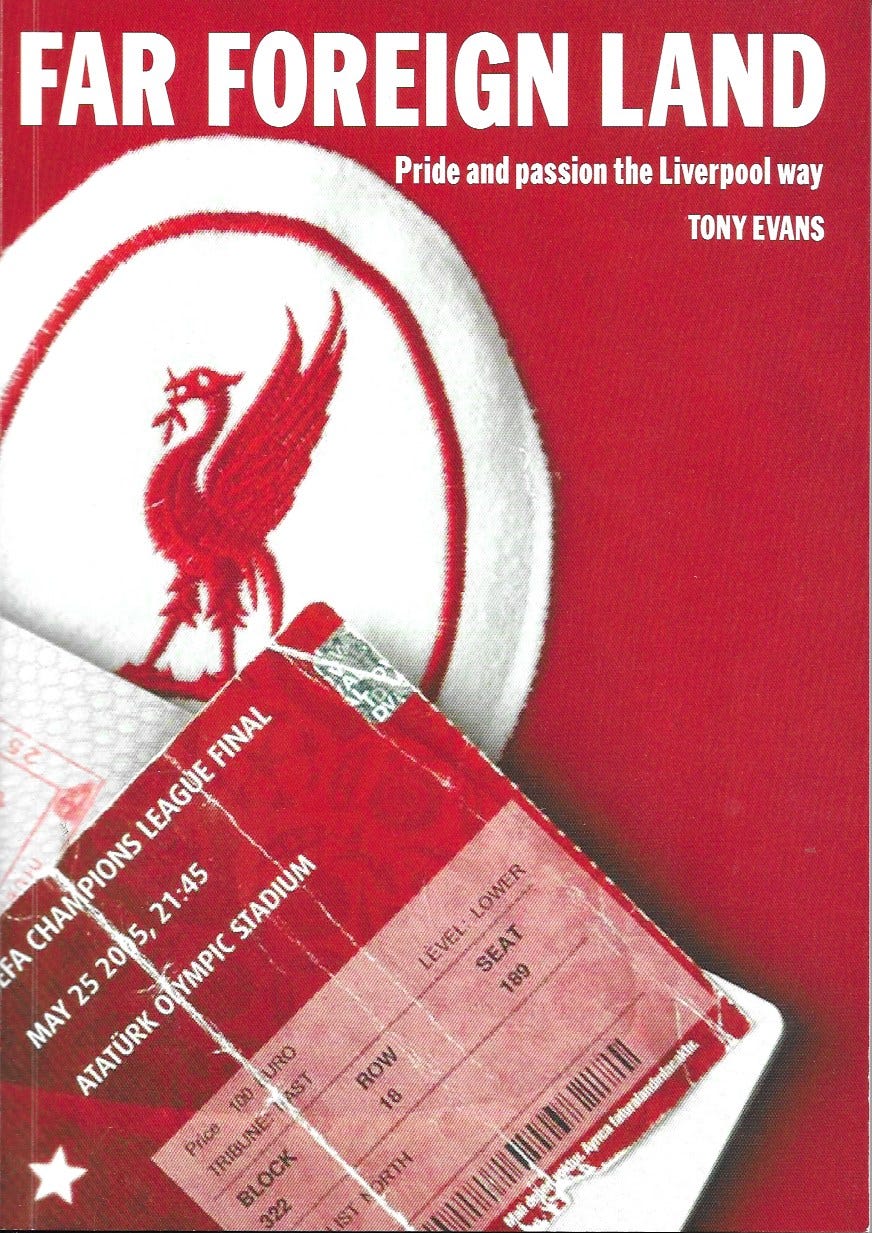

With the ticket in my possession, I began to have sympathy with Dave. You have to check it is still nestling in your pocket every couple of minutes.

It was a release to be certain of entry to the match. But there were other releases that were more pressing. All hell was breaking loose in my lower intestine and, before we set off for the stadium, a visit to the toilet was necessary. There was no waiting.

Confronted with a hole in the floor, I assessed the options. The trousers I was wearing were khaki but light enough not to risk in a splashback situation – especially with a dodgy knee. They had to com off completely. Then it took some gymnastics to accommodate the painful joint in a contorted squat. Now, safe in the knowledge that there would be no disaster, I could, er, relax.

And then the realisation hit home. There was no toilet paper. Now this was ugly.

Unhooking my trousers from the hanger on the door, I went through the pockets looking for tissues. None. I did have paper. A match ticket.

That was not really an option. And money. Shit.

Then the wad of two million lire notes began to look enticing. The upside was that they were next to worthless. The downside was that they contained Ataturk’s image and any Turk worth his name would tear me a new arse if I dared do the unthinkable.

But there was no way out. ‘Sorry Kemel,’ I whispered, ‘It’s just the cost of living.’And, so to speak, I wiped the slate clean.

Outside, the boys were preparing to get taxis to the ground. Yes, I agreed, we should get away from here.

I told Dave what happened. ‘You’ll get the cash back,’ he said. ‘It’s a legitimate business expense.’

Ah well, off to the ground.

There was a queue for taxis and, while we were waiting, a text message arrived. Someone we knew was up at the stadium and told us that the roads were blocked already. There was urgency in the words. ‘Get moving now,’ the message said. ‘Or you’ll miss the kick-off.’ It was four hours before the scheduled start of the game.

Still, we were expecting plenty of entertainment. Uefa had promised a ‘Fans’ Festival’ outside the ground as an incentive to arrive early. We were suspicious but felt that there was no option but to head for the Ataturk.

It was a long journey made tense by the driving style of our cabbie. Like many of his colleagues, he did the opposite of what was expected by his passengers. A light turns red up ahead? A quick injection of acceleration will liven things up. Oncoming traffic? Well let’s see whose nerve breaks first. It was ours

The driver took our gasps and comments as approval and grinned wildly, accepting the praise. Thankfully, the stunt-driving session came to an end. On the minus side, that was because the traffic was backed up and we were barely outside the city centre. It looked like being a long journey.

All around us were other cabs filled with Liverpool supporters, most of whom had displayed more foresight than us. They had slabs of beer with them, merrily drinking away the journey. Foolishly, we had neglected to bring provisions.

It was a huge, creeping procession, with people hanging out of taxis, minibuses and coaches, waving flags and singing and the population of Istanbul came out to enjoy the parade. The crowd was three or four people deep in some places and children ran alongside the cars handing out cardboard fans, presumably meant to help us cool down in the early-summer heat.

I suggested we pile them up to make a fire, because the temperature had been dropping all day and I was sure that there would be plenty of Scousers dressed for the tropics who could die of exposure over the next few hours. I was one of them.

More than sixty minutes into the journey, we left the built-up areas and took a brand-new road – the tarmac was still black and shiny – through a landscape that was eerily familiar. ‘Wasn’t that Myra Hindley with a spade back there,’ someone said. Could have been, because this was moorland of the bleakest sort, with one highway running across it.

And that road was blocked. People had already abandoned their vehicles and were walking. We asked the driver: ‘How far?’ He shrugged. The meter was running and we were being lapped by pedestrians. And they were weighed down by the 24-packs of beer they were carrying.

Al knocked on the window. The other group had ditched their taxi some half a mile back. ‘It’s about a mile and a half,’ he said. ‘You can just see it over there.’ He was right. The roof of the stadium was just visible in the distance when we got out of the car.

By now there was a wholesale evacuation under way. The hard shoulders were crammed with supporters and more had scrambled over the median barrier to walk against the flow of traffic heading away from the ground.

From a small hillock we looked over the scene. With the flags and banners unfurled, I was again struck by the thought that this is how a medieval army must have looked. Cows and goats scattered in their wake and the clarion call of Ring of Fire trilled up and down the rag-tagtrain. It was cold and the mud was ankle deep but we had been marching for 20 years in this direction and this was no time to stop.

A mile farther on the surrounds of the stadium became visible. We could not believe the number of people who were already there. A massive crowd was installed at the back of one end of the ground and occasionally a chant slipped through the wall of noise created by circling helicopters.

Our entire allocation of 20,000 appeared to be here and yet there were untold thousands still milling around the tourist sites in the city centre when we left. How many Liverpool supporters were here? And where were the Milanese?

The full horror of the Fans’ Festival dawned on us during the final half-mile of the yomp across the moors. There was a band on a stage, singing and plenty of portable toilets. And that was about it.

There was no food available and certainly nothing to drink. We wandered around on the edge of the crowd and even the programmes had sold out. No refreshments, no programmes and a drunken singer doing a Jimmy Tarbuck act on stage. Were Uefa trying to start an uprising?

‘Anyone lookin’ for a ticket? Fella with a spare to the left of the stage.’

he laughed. He was the only one that thought it was funny. Boos rang out, so he played Ring of Fire.

Oh, there were also some PlayStation consoles. Great. Just what a football fan wants before the Champions League final. Let’s warm up with Sonic the soddin’ Hedgehog.

All a supporter wants is a ticket for the match, a ground that’s easy to get to, places to eat and drink and enough points of entry at the stadium so that everyone can turn up in the half-hour before kick-off and get in easily. The efforts by Uefa to introduce fell-walking, concert-going and video gaming into the simple ritual of going the match shows how out of touch the people running the game are with those who pay to watch it. By now we were cold, hungry, frustrated and angry.

Frankly, it wouldn’t have taken much to start a riot in these conditions. And, to judge from the queues to get into the actual stadium, we might easily miss the kick-off anyway, even though there were still two hours to go.

We split up and headed towards our various gates. There was little left to be said. I nodded to Dave. ‘This is it,’ I said. ‘Yeah,’ he replied. All those years, all that abuse, all those hopes… ‘See you here, after.’

The rest were all behind the goal, but I was off to the side. There seemed to be chaos around my turnstile and it was easy to see why. Many of those in Liverpool shirts were from mainland Europe, a continent where the concept of the queue is unknown. A German, for example, will assume that you are standing in a line of people because you enjoy it and will walk to the front. Scandinavians make a similar assumption.

To do this around freezing, underfed and muddy Scousers invites a rebuke of the harshest sort and there was plenty of this going on. It was unbelievable. It took a serious effort by the authorities to turn the happiest crowd of people in the world into a surly bunch simmering with rage, but the Turks and Uefa achieved it.

Events at the gate helped to lighten the mood. The computerised entry system was clearly predicated on the chaos theory and, after the initial dispiriting few minutes, the absurdity of the situation stumbled into the comic realm. A barcode on the ticket was supposed to trigger the turnstile. But, of course, the supporter was not trusted to do this, so a Turkish steward first took the ticket, scrutinised it for a good 30 seconds to make sure it was not a fake and then scanned the barcode before motioning the fan forward. At this point, the supporter walks into the barrier and is halted by an immovable object. The computerised entry system simply did not work.

So the steward examines the ticket again. This time for longer, flipping it over to check its reverse. Yes, it’s real, so he moves it over the scanner again. The gate stays firm. They shall not pass.

Another period of reflection leaves the steward bemused. Finally, he tears off the stub in traditional style and manhandles the gate open. Each of these little vignettes took four minutes. I know. I timed the bloody thing. Seven times.

‘It’s not going to work, just push the turnstile and save us the grief,’ I said. But the Turk was tied to the ritual. He could not break the established methods. All you could do was take a deep breath and wait. It was still early. If this was happening 10 minutes before kick-off, our boys would break the gates down – and the heads of anyone who tried to stop them.

You could see why there was no beer available: Uefa couldn’t organise a piss-up in a brewery. Except, of course, for their own. Because inside the ground, in tents a mere 20 yards from the salmonella factories that were producing semi-raw kebab burgers at extortionate prices for the paying fans, were the corporate guests, eating food of the highest quality and swilling alcohol in voluminous quantities.

Some supporters in shirts lurked enviously by the entrance to the hospitality tents. Those inside, dressed for the theatre or the opera, had sneers on their faces as they surveyed the shirt-wearers. Security made things easier for the privileged by moving along the unwashed. Once in the ground, I could afford to be sanctimonious again and sneered at the whole idea of corporate entertainment.

After the great lengths that the authorities had gone to outside to keep the two sets of fans apart, there was no segregation in this area. The Milan fans were visibly shocked when they entered the stadium to see red shirts everywhere. They needn’t have worried. All the ire was directed against those running the sport. The Italians were sharing our suffering.

The pitch looked beautiful but the real sights were in the stands. Red banners were everywhere. Some simply said ‘Liverpool’ or carried the name of a favoured pub, but others were more esoteric. Would the casual observer, for example, read the words ‘The distance between insanity and genius is measured only by success’ and know immediately that this was a Liverpool banner?

The use of Shanklyisms means that our standards project something more than mere support for a team. ‘The only way to be truly successful is by collective effort’ is a philosophy for life rather than a football flag. Such phrases, invariably in white lettering on a red background, were everywhere, spicing up the simpler ‘Red Army’ type flags.

The display of banners is a phenomenon that developed in the 1990s. When we were last in a European Cup final, flags were considered uncool, unless they were very funny.

A classic 1980s vintage banner mocked Ron Atkinson, the Manchester United manager at the time, for his dress sense. It simply said: ‘Atkinson’s long leather.’ If you don’t understand it immediately, it is not worth attempting to explain it. You never will comprehend.

Now, small groups of travelling Liverpool fans make it a point of pride to carry their own flag. At the League Cup final against Chelsea earlier in the season, it made for a marked contrast between the two groups of supporters. Chelsea had their Union flags and crosses of St George with the team name on the horizontal bar. They must have thought for a long time before going down that route.

At the Liverpool end, the energy and imagination that had gone into the creation of the flags showed how important the football club is to the fans. The sense of history and belief was written down for the Londoners to envy. It was here in Istanbul, too.

It was sad, however, to see empty seats in the ground. A significant number of Milan’s tickets had not been sold. The expense of getting to Turkey and the vague fear of Liverpool supporters had an effect.

More galling is Uefa’s habit of leaving vacant the front rows of seats all around the pitch, so supporters and their banners do not get in the way of the advertising boards. What other sport would leave empty the seats most likely to be seen by the television viewer during its showpiece event?

The casual observer gets the impression that the game did not sell out. Marketing men operate on a different logic system to the average fan.

The Milan supporters had promised a spectacular, choreographed display before the match. Just before kick-off, they did their stuff. Very nice. The Liverpool fans sang You’ll Never Walk Alone throughout it and upstaged the Italian show with flags, scarves and banners on three sides of the ground.

Time was nearing. Suddenly it didn’t feel so cold. Out came the teams. It felt like 20 years had never happened.

‘They all laughed at us,

They all mocked us,

They all said our days were numbered,

But I was born to be Scouse,

Victorious are we,

So if you’re gonna win the cup,

You’d better hurry up…’

But those around me didn’t know the song. Or were too busy singing

Ring of Fire.

Well, here we go…

Read Chapter 17: The Liverpool way

Order Far Foreign Land here: Cost £10 UK, £15 Europe, £18 Rest Of World. All including postage

For those interested in the culture of Merseyside, try my non-football novel. Good Guys Lost, an epic of Liverpool life set from the 1960s to the 2010s